“There are those who seem to have nothing else to do but to suggest modes of taxation to men in office.”

Conservative Prime Minister Robert Peel, in the House of Commons, 1842

In Nigeria, digital currencies used for electronic transfers have driven out cash, leading to hoarding of banknotes and their commodification. This shift to a cashless economy raises questions about how taxation can be affected. This section explores the outcomes of a cashless economy related to taxation. But first let us glance at the process of money creation and to the theorem of Gresham.

Process of creation money

We have seen in the part two that commercials banks play a tremendous role in transactions as stakeholders use them as intermediaries. In most countries, the majority of money is mostly created as M1/M2 by commercial banks making loans. Contrary to some popular misconceptions, banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and do not depend on central bank money (M0) to create new loans and deposits.

May be the policy of cashless economy initiated by the CBN can lead commercials banks of Nigeria to create more money for the economy because it will increase their prudential rations. While commercial banks play a significant role in the creation of money, the Theorem of Gresham provides insight into how different forms of money interact within an economy.

Theorem of Gresham

The Law or Theorem of Gresham, after Sir Thomas Gresham, who clearly perceived its truth many centuries ago, expressed briefly is that: bad money drives out good money, but that good money cannot drive out bad money (Jevons, 1875).

Gresham’s remarks concerning the inability of good money to drive out bad money, only referred to moneys of one kind of metal by its time, but the same principle applies to the relations of all kinds of money, in the same circulation. Gold compared with silver, or silver with copper, or paper compared with gold, and today digital money compare to banknotes are subject to the same law that the relatively cheaper medium of exchange will be retained in circulation and the relatively dearer will disappear.

It seems like digitals currencies used by electronic transfers have driven out cash in Nigeria. Banknotes are hoarded. They have gained such a value that they have become themselves commodities that are sold. (For instance, customers at some places were paying up to 20% of an amount, just to get cash[1]).

In this context, how taxation can be affected by cashless policy?

Outcomes of cashless economy related to taxation

WATAF as regional tax organisation deals with different stakeholders that seem have contradictory interests. WATAF interact with Tax Administrations in West Africa, Government Institutions, Corporate Taxpayers and General Public to cite a few. All these bodies are somehow affected by cashless economy. Nevertheless, how can they take advantage of such reform? And what are the challenges? Here are some outcomes of cashless economy related to taxation.

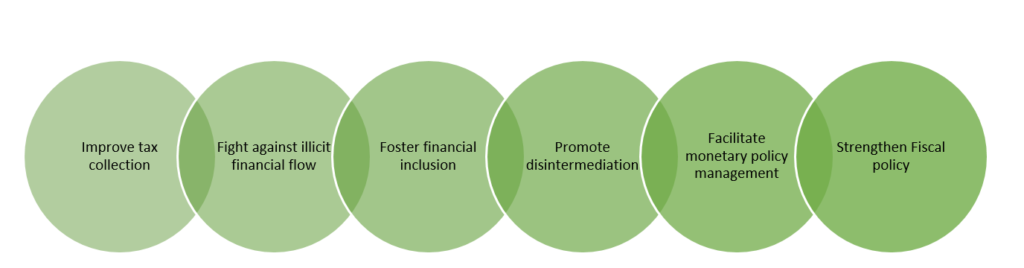

Figure 6: Some outcomes of cashless economy related to taxation

Source: Design by author

Improve tax collection

For those who pay by direct deposit to their bank account and use electronic payment methods for most of their payments, the tax implications of moving to a fully digital economy are negligible. In highly technological countries, they are already working on high digitalised tax systems, leaving little room for tax evasion, unless of course you are lucky enough to receive a large amount of cash. (The case of the Vice-President of the European Parliament, Ms. Eva Kaili, from whom 600 000 euros were retrieved during investigation is a nice exemple[2]).

There are certain businesses, both illicit and legitimate, that depend on cash, and digital currency will undoubtedly impact them in different ways. We are already getting the benefits of such policy with the reduction of outlaws’ behaviors[3].

Legitimate tax-paying businesses may find the transition to a cashless economy a welcome relief, as the time and effort required to control cash flow is eliminated or drastically reduced. Meanwhile, illegal companies hiding cash for the purpose of tax evasion will phase out the cash and gradually use cryptocurrencies as a vehicle to move ill-gotten gains.

Fight against illicit financial flow

Illicit financial flow, money laundering and tax evasion, however, have more to do with false contracts and billings that may still be fraudulent regardless of the form of payment. In this regard, Tax Administrations should intensify their efforts to upgrade their information systems to better take advantage of this cashless economy policy.

According to Turrin (2021), cashless economy policy is a significant selling point to regulators, and a significant perceived advantage of digital currency. This policy can “bring in cash from the cold” into the monetary system and could help ending money laundering. Conversely, he argues that its effectiveness in this role is somewhat overstated. History suggests that the technological acumen of those seeking to avoid taxes will simply ratchet up to match the government’s digital efforts. Cryptocurrencies are already in use for hiding and trafficking illegal funds. That these efforts will only increase as cash is weaned out is a given.

Foster financial inclusion

Another major benefit that the digital economy can offer is safe and secure way to store currency for those who are new to banking. Hiding money under the mattress will belong to past, as carrying large rolls of cash and the security risks that come with it. According to Statista report published in September 2022, 45% of the population in Africa sub-Saharan was unbanked in 2021[4]. Unfortunately, we do not have the percentage of the underbanked. The cashless economy offers these populations a safe and convenient way to join the financial system.

With inclusion, the identification of taxpayers will be easy and will help to broaden the tax base, which will certainly increase Domestic Revenue Mobilisation (DRM) allowing the government to increase its expenditures and the redistribution of wealth to all citizens.

The tremendous success that China had in drastically reducing its unbanked population with version 1.0 digital currency products and the effect on enhancing financial inclusion is a good example. World Bank statistics show that between 2011 and 2014, the percent of Chinese adults with a “store of value” account increased from 64% to 79% due to the availability of mobile payment systems (Turrin, 2021).

Promote disintermediation

For retail users, of all the potential benefits of digitals currencies, disintermediation is potentially the most beneficial. They allow instant digital payment to a receiver of choice, bypassing intermediaries. This means savings, depending on how much these intermediaries’ charges.

Cashless economy is a profound systemic change that put pressure on the entire lines of business within banks and payment services. We have witnessed the long queues, weeping, uproars, demonstrations and fight in front of almost all the branches of commercials banks during this transition coupled with Naira swap from old notes to the new one in Nigeria. While most retail payment users would welcome disintermediation, it would be a severe blow to all companies in the payment sector which extract “rent” for transferring cash.

The disintermediation will lead to a smooth flow of currency that will enhance exchange and bring to economy expansion on which taxes can be levied for the benefit of all.

Facilitate monetary policy management

Central banks fine-tune interest rates and the money supply to target inflation or deflation in an economy according to Turrin (2021). Digital currency itself could allow for immediate adjustments to accommodate a country’s monetary policy. A change in interest rate could be as instantaneous as the press of a button on the central bank’s computer. The ability of a central bank to enact negative interest rate policies would be just as easy.

Digital currencies may allow interest rates to be adjusted based on a number of factors that currently do not work. For example, rates may vary depending on whether the currency is held by a company or an individual, or which country is involved. The possibilities are endless. They all depend on what data is collected in the process and whether that data is transmitted back to the central bank. Digital technologies make it possible to take into account monetary policy considerations that go far beyond the universal policies of analogue systems.

With a full monitoring of economy trends, it will be simpler to predict tax revenue accurately. It will be easier to measure the effectiveness of not only Tax Administrations but also government actions, because stakeholders such as Civil Societies Organisations (CSOs) may have tools to weigh them.

Strengthen fiscal policy

COVID-19 brought economic suffering to many. Governments responded with stimulus cheques in some countries. At the same time, the long-term nature of unemployment in the wake of the crisis and the long stand impoverishment in developing countries is leading to serious discussions about the provision of universal basic income (UBI).

Some countries are already engaging in this process. Spain announced it would implement a “national minimum income” of 462 euros per month (Turrin, 2021), with increases depending on the number of family members. Digital currencies would make the payment of benefits of any form to the citizen both cheaper for government and more efficient.

This will also help to master tax expenditures in countries which is a burdensome exercise now. We can safely say that digital currency is the “digital Rosetta stone” that can be given to taxpayers as reward if everything functions well.

In this last part of the series, we explain the process of money creation by commercial banks through loans and highlights the Gresham’s Law. We discuss the influence of a cashless economy on taxation, including improved tax collection, the fight against illicit financial flows, increased financial inclusion, disintermediation, facilitation of monetary policy management, and strengthening of fiscal policy. We emphasize the benefits of a cashless economy, such as reduced tax evasion and increased efficiency in government payments, while acknowledging potential challenges and the adaptation of illegal activities to digital currencies.

General conclusion

The adoption of a cashless policy has significant implications for taxation and revenue mobilisation. While it offers benefits such as increased transparency and efficiency, it also poses challenges such as the need to adapt tax systems and compliance measures.

The five series explore the concept of money, taxation, and cashless society. They provide a brief history of money and taxation, their origin, properties and functions. The series also mention the classification of taxes into direct and indirect taxes and explains the principles of taxation as set out by Adam Smith in his famous four canons of taxation which remain relevant today and provide a framework for designing a fair and efficient tax system.

These publications provide an in-depth analysis of the evolution of money and taxation, and how it has shaped our society. The move towards a cashless society is also discussed, highlighting both its benefits and challenges. Overall, effective management of taxation in a cashless society requires collaboration among various stakeholders, including tax administrations, government institutions, corporate taxpayers, and the general public.

References

Adam Smith (1776), The Wealth of Nations. The Havard Classics

Bernardo Bátiz-Lazo, Thomas Haigh, and David. Stearns (2014). How the Future Shaped the Past: The Case of the Cashless Society. Enterprise and Society

Brian Duigna What Is a Cashless Society and How Does It Work?

What Is a Cashless Society and How Does It Work? | Britannica

DK publishing (2017). How money works. Dorling Kindersley Limited DK, a Division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Ludwig von Mises (1912). The Theory of Money and Credit, Translated from the German by H. E. Batson, Liberty Fund Indianapolis, 1981.

Dominique Rambure & Alec Nacamuli (2008). Payment Systems from Salt Mines to the Board Room. Palgrave Macmillan

Stephen Smith (2015). A very short introduction to taxation. Oxford Academic, https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780199683697.003.0001

William Stanley Jevons (1875). Money and the Mechanism of Exchange. New York: D. Appleton and Co. 1876.

Richar Turrin (2021). Cashless: China’s Digital Currency Revolution. Authority Publishing

Léon Walras (1874) Éléments d’économie politique pure, ou théorie de la richesse sociale – Théorie de la circulation et de la monnaie. Guillaumin

[1] https://www.bellanaija.com/2023/02/new-naira-notes-cashless-economy/

[2] https://greekreporter.com/2022/12/09/qatar-world-cup-corruption-eva-kaili-eu-parliament/

[3] https://guardian.ng/opinion/benefits-of-naira-redesign-cash-limit-and-swap-policies/

[4] https://www.statista.com/statistics/553180/distribution-of-unbanked-population-by-region/

Nyatefe Wolali DOTSEVI: Tax Research Manager, WATAF Secretariat

Views Today : 9

Views Today : 9 Total views : 8029

Total views : 8029