In the previous article “Tax actions for preventable death (Part I)”, we asserted that in the quest to fulfill its multifaceted role, taxation has emerged as a potential solution to the escalating public health crisis triggered by the consumption of mephitic products such as tobacco, cigarettes, etc. This crisis is a primary concern for public health institutions worldwide, including the World Health Organization (WHO). In the circle of noxious commodities, rising as a giant pedestal above the insidious threat are high sugar foods. Their consumption of soft and energy drinks has increased dramatically over the past several decades. These types of beverages are constantly consumed by a significant percentage of the population, irrespective of gender, age, or socio-economic conditions. These unhealthy brews are believed to improve attention and performance. Although they offer significant energy and a pleasure of taste, numerous studies have revealed that they may produce significant health damage, especially when consumed in high amounts and for a long time according to the Science of beverage, volume 10[1]. The most well-documented health issues refer to metabolic disorders, obesity, dental damage, and cardiac arrest[2]. First of all, how did those creeping menace spread throughout the Gulf of Guinea?

According to Professor Nicoué Gayibor in the two volumes of “The Ewe (Togo, Ghana, Benin) – History and Civilization”[3], though tobacco was the flagship product smuggled by European slave traders among others [link to part 1 here], the human traffickers also introduced sugar that superseded most of the natural sugary plants such as Synsepalum dulcifium that was in use across the region[4]. It is worth noting that the highly physical activities of our genitors helped them overcome the setbacks correlated with the consumption of sugar, unlike the exceedingly sedentary lifestyle of the current generation. Furthermore, the aggressive marketing designed by high sugar brewers such as John Pemberton in the late nineteenth century, after replacing alcohol in the Pemberton’s French Wine of Cola[5] with sugar, yielded its fruits by luring many into the overconsumption of soft drinks worldwide.

Soft drinks are high in sugar content and acidity. Each gram of sugar contains 4 calories. In addition, they supply energy only and are of little nutritional benefit, according to Bere et al. (2008)[6] corroborated by Bucher and Siegrist (2015)[7]. The United Kindom’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) posited in 2015 that several studies have shown that soft drink consumption can contribute to detrimental general and oral health impacts on children and adolescents, including overweight, obesity, increased risk of type 2 diabetes, dental caries, and dental erosion[8]. How can taxation contribute to curbing such baleful trend?

Various measures have been implemented in multiple countries worldwide to address the issues of obesity and dental caries. These efforts encompass prohibiting the availability of soft drinks in educational institutions, regulating the promotion of soft drinks, and implementing a levy on soft drinks containing sugar. Many governments have enforced bans on the sale of sugar-sweetened soft drinks in schools. The United Kingdom, for instance, implemented stringent regulations regarding the sale of soft drinks in educational settings back in 2007. Beverages with added sugar, which also include energy drinks, are not allowed. Additionally, some schools have prohibited their students from bringing energy drinks onto the premises from external sources[9].

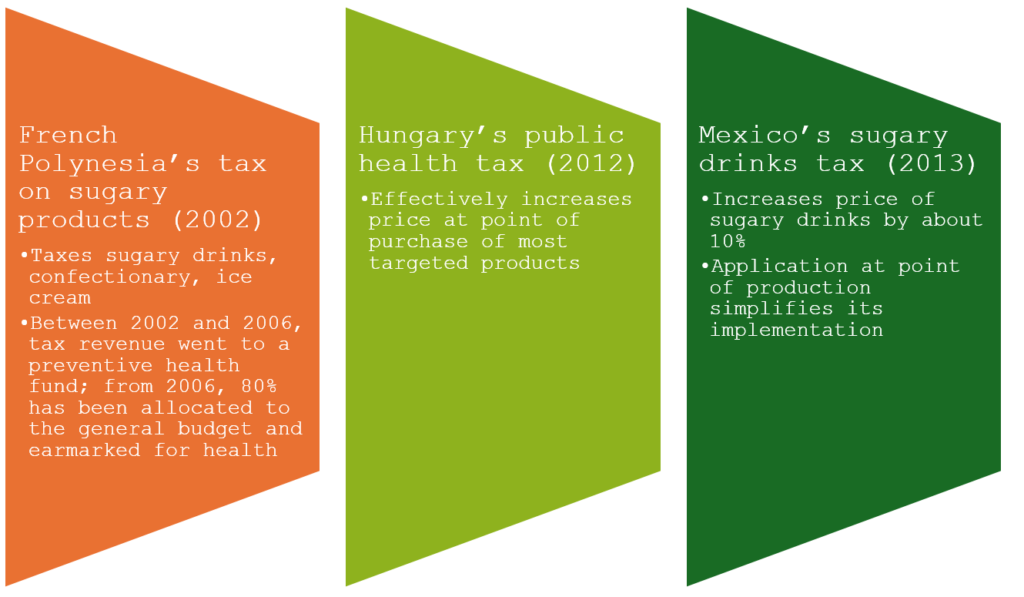

Furthermore, several governments across various countries, such as the UK, have implemented strategies to limit the promotion of sugary beverages to children on digital platforms and TV, as highlighted by Al- Mazyad et al. (2017)[10]. This proactive stance has also been observed in Australia, Sweden, and Belgium according to Story and French (2004)[11], where measures have been enforced to forbid the advertising of high-sugar and high-fat products during programs aimed at children. Moreover, some jurisdictions globally, including French Polynesia, Hungary, and Mexico, have taken significant actions to address childhood obesity and dental problems by imposing taxes on sugar-laden soft drinks, as emphasized by the World Cancer Research Fund International[12] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Taxing sugary drinks in various jurisdictions[13]

Source: World Cancer Research Fund International.[14]

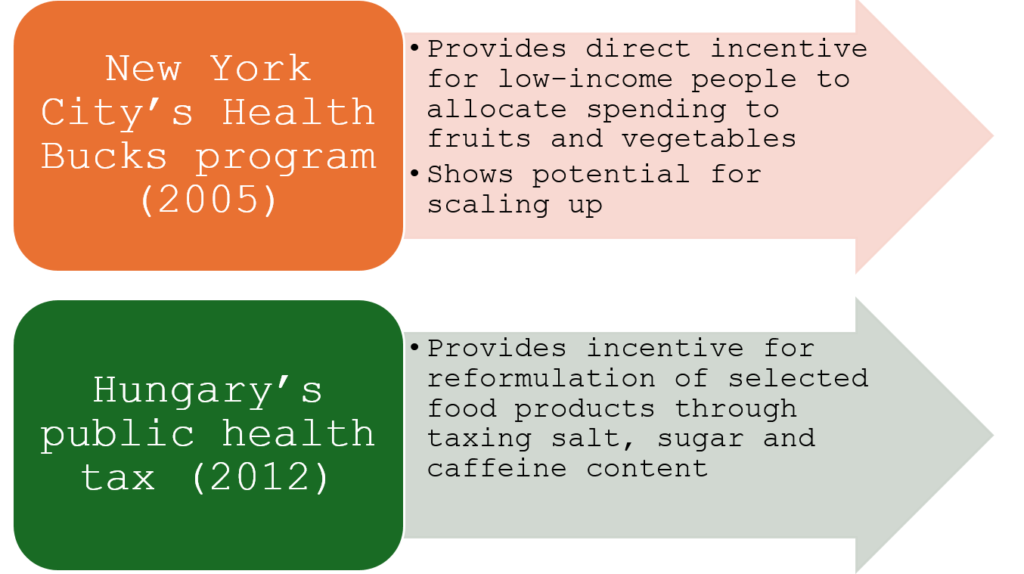

If some jurisdictions akin to the above, may opt to use what Burton and Sadiq (2013)[15] call the negative form of the term first used by Stanley Surrey in his speech on 15 November 1967[16]: ‘tax expenditure’ is an oxymoron intended to highlight the incorporation of ‘spending’ rules within the ‘taxation’ law; others adopt either the positive form or both like Hungary.

Figure 2: Tax expenditure to encourage healthy food consumption in some jurisdictions

Source: World Cancer Research Fund International[17].

As result, Colchero et al. (2016)[18] found a 10% decrease in the consumption of sugary drinks and a 4% rise in the purchase of healthier alternatives like bottled water in Mexico following the introduction of a soft drink tax in 2014.

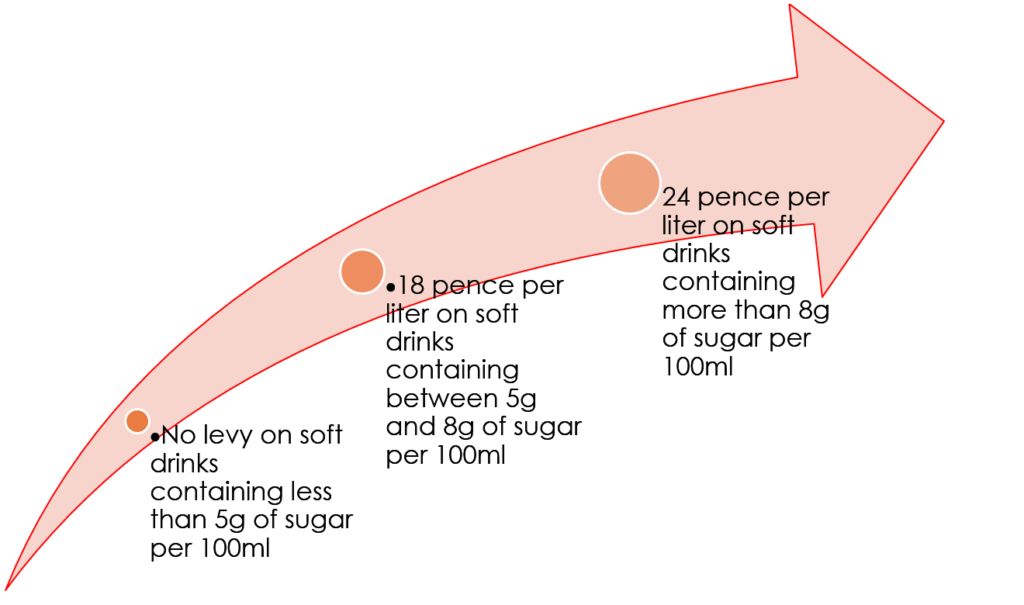

To help tackle obesity, type 2 diabetes, reduce bone density and bone loss, dental caries, dental erosion, etc. by reducing the consumption of soft drinks with added sugars, African countries in general and specifically West African countries, through ECOWAS, for instance, can implement taxes or levies such as the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL), or ‘sugar tax’, which is a levy applied to UK-produced or imported soft drinks containing added sugar. The SDIL was announced in George Osborne’s March 2016 budget, came into force in April 2018[19], and was expected to reduce the consumption of sugar-containing soft drinks by 1.6% by encouraging soft drink manufacturers to reduce the sugar content of their products[20].

The levy is paid to HMRC by the packager for drinks produced in the UK or importer for drinks produced overseas at the following levels:

Figure 3: Amount paid as SDIL

Source: Soft drinks industry levy.[21]

Nevertheless, some exemptions apply, including milk-based drinks, juices, and drinks produced by smaller businesses.[22]

Overall, the West African Tax Administration (WATAF), in collaboration with a multitude of stakeholders, is keenly prepared to support endeavors aimed at bolstering endeavors to reduce avoidable fatalities. WATAF’s enthusiastic stance underscores its commitment to foster economic development in the region, thereby contributing to the broader global agenda of improving the health of the region.

[1] Grumezescu, A. M., & Holban, A. M. (2019). Sports And Energy Drinks, Volume 10: The Science of Beverages. Elsevier.

[2] ibid

[3] Gayibor, N. (2021). The Ewe (Togo, Ghana, Benin) – History and Civilization. Lomé: Presse de l’Université de Lomé.

[4] ibid

[5] Future Coca-Cola. Lester, D. (2016). How they started Global Brands, How 21 good ideas became great global businesses. Crimson Publisher.

[6] Bere, E., Glomnes, E., Te Velde, S., & Klepp, K. (2008). Determinants of adolescents’ soft drink consumption. Public Health Nutrition. 11 (1).

[7] Bucher, T., & Siegrist, M. (2015). Children’s and parents’ health perception of different soft drinks. Br. Journal of Nutrition. 113 (3).

[8] Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition., 2015. Carbohydrates and Health. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-carbohydrates-and-health-report Accessed on 12 May 2024

[9] British Soft Drinks Association, 2016. Leading the way. UK soft drinks annual report. Available from: https://www.britishsoftdrinks.com/write/mediauploads/publications/bsda_annual_report_2016.pdf Accessed on 11 May 2024

[10] Al-Mazyad, M., Flannigan, N., Burnside, G., Higham, S., & Boyland, E. (2017). Food advertisements on UK television popular with children: a content analysis in relation to dental health. Br. Dent. J. 222 (3).

[11] Story, M., & French, S. (2004). 2004. Food advertising and marketing directed at children and adolescents in the US. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 1 (1).

[12] World Cancer Research Fund International. Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/PPA-FoodPolicyHighlights-21.pdf Accessed on 13 May 2024

[13] The Federal Government of Nigeria has expressed its readiness to raise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) from the current rate of 10 percent to 20 percent.

The SSB tax, embedded in the Finance Act of 2021, levies a N10 tax on each litre of all non-alcoholic and sugar-sweetened carbonated drinks, as part of efforts to discourage excessive consumption of sugar, which contributes to the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, diabetes, among others. Stakeholders have repeatedly urged the government to raise the tax, saying the current rate has not achieved the impact as SSBs as still affordable and consumption is still high. https://businessday.ng/news/article/nigeria-customs-leads-charge-to-tax-sugar-sweetened-drinks/ Accessed on 24 June 2024

Edozie Chukwuma, a representative of National Action on Sugar Reduction (NASR) in Nigeria, while stressing that sugary drinks were a leading cause of NCDs like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases as well as obesity which are also fatal, urged the government to increase tax on sugary drinks, and enact a pro-health tax that channels revenue from taxation of sugary drinks to funding of healthcare. https://guardian.ng/coalition-urges-fg-to-increase-sugar-tax-from-n10-to-n30/ Accessed on 24 June 2024.

Meanwhile, some nefarious businesspeople try to impose the purchasing of SSBs on their customers. The author was personally victim of such noxious attempt while purchasing packs of water, the supplier forcibly wanted him to buy soft drinks packs along otherwise she would increase the price of the water due to scarcity. The author paid higher price for the water and disregarded the SSBs.

[14] ibid

[15] Burton, M., & Sadiq, K. (2013). Tax Expenditure Management: a critical assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[16] Surrey, Excerpts from Remarks Before the Money Marketeers on the US Income Tax System – he Need for a Full Accounting in the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1968

[17] ibid

[18] Colchero, M., Popkin, B., Rivera, J., & Ng, S. (2016). Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: observational study. . BMJ 352, h6704.

[19] Sugar tax. Available from: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainer/sugar-tax Accessed on 14 May 2024.

[20] Grumezescu, A. M., & Holban, A. M. (2019). Sports And Energy Drinks, Volume 10: The Science of Beverages. Elsevier.

[21] Check if your drink is liable for the Soft Drinks Industry Levy. Available from:

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/check-if-your-drink-is-liable-for-the-soft-drinks-industry-levy Accessed on 14 May 2024.

[22] ibid

Nyatefe Wolali DOTSEVI: Tax Research Manager, WATAF Secretariat.

Views Today : 98

Views Today : 98 Total views : 37538

Total views : 37538