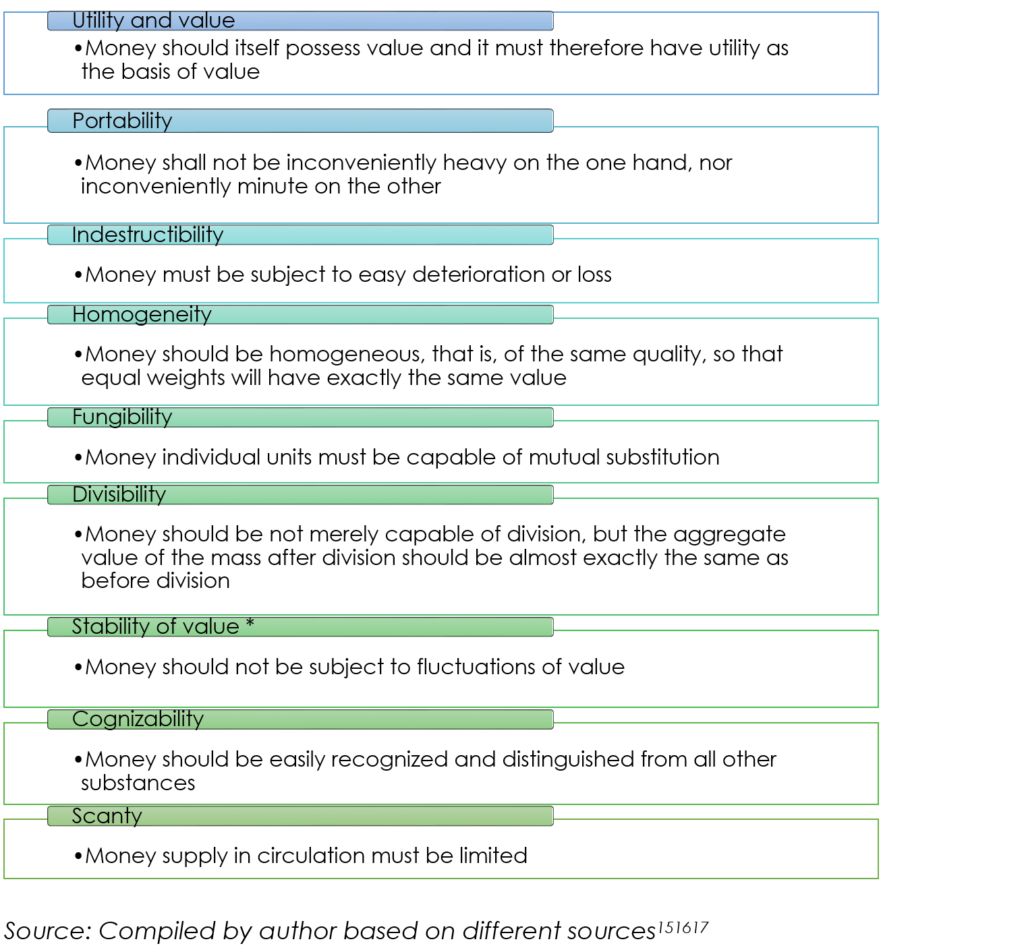

Whatever shape it takes, whether as a coin, a note, or stored on a digital server, money always provides a fixed value against which any item can be compared. To fulfil this role, money must possess some properties.

Properties of Money

Figure 3: Properties of money

Instrument of payment

The choice of a payment instrument represents a compromise between the various counterparties based on consideration of the features and benefits:

- ease of use and convenience for the debtor or the creditor;

- terms, conditions and execution time: the beneficiary, in particular, wishes to know when the funds are available for him to draw upon;

- ease of automation, not only for processing the payment but also transmitting the reason for the payment, or remittance information, to facilitate reconciliation;

- costs, in terms of fees charged to the initiator and/or the beneficiary, as well as processing costs to the service providers including the cost of liquidity;

- security, expressed in terms of authenticity, confidentiality and integrity: the assurance that the declared source is the true source and that no outside party could have seen and/or changed any of the data: amount, beneficiary’s name, references, etc. Another factor gaining importance with internet banking is non-repudiation: the inability for a counterparty to deny that it has taken a specific action; and

- auditability and traceability: the ability to prove that a payment has been effected and/or received, as well as facilities to track and trace the payment in case of delayed receipt or queries[4].

The stakeholders involve in the process are countless. However, we can list a few of them such as: central banks, commercial banks and service providers, government institutions, companies; corporate customers, retail customers.

Mainly, two factors influence their choices that are showed in the next figure.

Figure 4: Factors that influence payment instrument choice

Source: Design by author

- Circumstances: face-to-face when creditor and debtor are in physical presence of each other, as opposed to remote payments when mail and/or electronic transmission must be relied upon; and

- Frequency: occasional (or one-off) payments for shopping or, for instance, professional fees, as opposed to recurring payments such as mortgage repayments, insurance premiums or utility bills[5].

Inertia is a major factor in choosing a payment instrument. Habits die hard and any plan to shift customers from one method to another (e.g. moving to direct debits, cheque collection) will require a concerted effort by banks, regulators, industry bodies and consumer group for several years. This inertia is exacerbated by the fact that cross-subsidies between products and customer segments are prevalent and pricing is generally opaque, especially for individual customers.

No matter how circumstances or frequencies occur in the transaction between creditor and debtor, once a jurisdiction has it interest into it, the operation should be taxed. There is a well-known assertion stating that “follow the money for taxation”. Nonetheless what is taxation?

What is taxation?

Hence, what are taxes? Yes, we know. They are the money that is taken from us by the government for public expenditures and other purposes. But taxes differ from the money that we spend in other ways in two distinctive respects.

To endeavour a formal definition, taxes are compulsory payments, exacted by the state, that do not confer any direct individual entitlement to specific goods or services in return. The second part of this definition is fundamental, discriminating taxes from the prices, fees, or charges that could be levied on the sale of goods and services by the state or state businesses. While these, too, can generate public revenue, the fact that something is supplied directly in return for the payment inferring that they can be voluntary. The compulsory nature of taxation doubtless accounts for much public hostility (Smith, 2015).

After understanding the basics of taxation, let’s explore its features in contemporary tax systems.

Feature of taxation in contemporary tax systems

A key characteristic of taxation in modern tax systems is that taxation is ‘parametric’: in other words, it is governed by legislation which defines in advance the basis of individual tax liability (Smith, 2015). Typically, such legislation defines the tax base – it means, the aspects of economic activity that are subject to taxation, such as income, expenses or the value of property – and how an individual’s tax liability is calculated, in a clear and predictable way.

You may find through this link the prediction of some West African countries for this fiscal year gathered by WATAF (Finance acts of West African Countries in a crisis context).

Let us point out that Taxes have often been levied in the past in the arbitrary way and was not based on clear and stable principles (Taxation that is not properly governed by a legal framework that sets out how tax liability is computed can provide an undesirable spectrum of corruption). In this publication, WATAF shows the crucial role of parliamentarians in the process of amending budget or finance act (This is the season!!!).

In this section we explore the properties of money and the factors that influence the choice of payment instruments. We discuss the importance of ease of use, automation, security, costs, and auditability in payment systems. The stakeholders involved in the payment process are numerous, including central banks, commercial banks, government institutions, and retail customers. We also highlight the influence of circumstances and frequency of transactions on the choice of payment instruments. Inertia and established habits play a significant role in determining payment preferences. We made a transition to discussing taxation, defining taxes as compulsory payments to the state that do not confer individual entitlement to specific goods or services. We emphasize that taxation is governed by legislation and follows clear and predictable principles in modern tax systems.

In the next part, we will look at a succinct history of taxation.

[1] *Note about stability of value: The ratios in which money exchanges for other commodities should be maintained as nearly as possible invariable on the average. This would be a matter of comparatively minor importance were money used only as a measure of values at any one moment, and as a medium of exchange.

[2] (Jevons, 1875) see references

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money

[4] (Rambure & Nacamuli, 2008) see references

[5] idem

Nyatefe Wolali DOTSEVI: Tax Research Manager, WATAF Secretariat

Views Today : 40

Views Today : 40 Total views : 63372

Total views : 63372